Field stations are relatively few and far between. Rarer still is a report of what occurred on the first night of the start of a field station. At Harkness, such a description is provided by R.B. Miller, the first graduate student at the field station (M.Sc. 1937; Ph.D. 1939). Along with Miller was a young Fred Fry and his wife. In his book, Cool Curving World, Miller describes what it was like to be at the site and what they did to pass the time that first night. The following passages are taken from Chapter 2, A Cool Curving World by Richard B Miller, 1962. Longmans Publisher, Toronto.

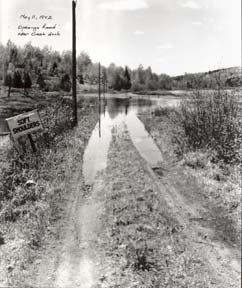

(Page 5) My first visit to Algonquin Park was in the spring of 1936. I was a very junior member of a party of three. The senior members were Fred (Fry) and his new bride. We were on our way to make arrangements for the establishment of the Ontario Fisheries Research Laboratory’s new summer headquarters on Lake Opeongo. We drove up in a 1925 seven-passenger Studebaker sedan. It was square and had blinds on the windows. It was a wonderful old car; its gear ratio would put a modern pick-up truck to shame as it stolidly plowed through mud-holes in top gear. We made good use of this mud-crawling ability. The road into Algonquin Park was, at that time, little more than a trail, with many low, swampy places, sharp curves, and abrupt little hills. The frost was coming out of the ground and the crooked ruts were full of water with a thin ice crust from the night before. The old car lurched violently from side to side with uncomfortable abruptness. However, I was so interested in the new country that I was scarcely aware of the drive; furthermore, being from Saskatchewan, I was used to mud roads; and anyway, Fred was driving.

(Page 6) When we finally arrived at Lake Opeongo it was getting late and cold. The trail, which had become progressively more primitive as we neared our goal, suddenly petered out completely on the edge of what appeared at first to be an enormous muskeg. It was a broad, flat, depressed area, almost covered with low shrubbery – alders, willows, and acres and acres of sheep laurel and Labrador tea. Here and there patches of steaming water were visible; as the evening chill grew sharper a mist rose off the swamp and the made the air damp and raw.”

We got out of the car. The smell of spring in the North was overwhelming. It is a smell hard to describe, a compound of breaking buds, very early blossoms, and rich, wet earth – invigorating and yet, somehow, strangely nostalgic and subduing. We were also overwhelmed by insects – vast, angry clouds of mosquitoes and blackflies. Mosquitoes I knew of old from the prairies, but the blackflies were a new experience. Soon rivulets of blood ran down behind our ears, into our collars, and from eyebrows into eyes. Fred had grown up on an Ontario farm, and I was used to the less pleasant aspects of the out-of-doors; the person who really must have suffered was Fred’s wife – a city girl on her first trip into the woods, and expecting a baby as well. I never heard her complain; in fact she looked more unhappy later that night, after we were settled and fairly comfortable, when Fred insisted on reading aloud a chapter of the Origin of Species.

The trail ended at a small landing which struck out into the swamp. Tied to it was an ancient, battered open launch with a model-T Ford engine. This, announced Fred, was the Fish Lab boat. We squished around in the damp moss transferring contents of the car to the boat. Then, abandoning the sturdy Studebaker, we pushed out into the wet tangle of brush to find a narrow, winding, brush-free river, looking black, mysterious and sinister in the fading twilight. This led to Lake Opeongo.

(Page 7) The Model-T engine suddenly chugged into life, Fred leapt from it to the tiller, and we were off. Because of the dim light, the numerous bends, and the narrow channel, we seemed to be travelling at a furious pace. Eventually we emerged from the creek into a good-sized open piece of water which I later learned was the south arm of Lake Opeongo. Here we found a forestry station and a travelers’ camp shelter. We docked, made a rather primitive camp, ate a cold meal, and went to bed on the ground. It was bitterly cold, and I was a long time generating enough heat to feel sleepy. The last thing I remember is Fred reading Darwin by the light of a small, smoky kerosene storm-lantern, and the incessant bellow of the frogs.

(Page 9) Our first day was spent in acquiring the use of a frame building, and old summer cottage, on the lake shore, and moving our provisions and equipment into it.

(Page 10) In a week or so we were joined by other members of the lab: Ray (Langford), a student of plankton – like Fred, a Ph.D. and a member of a university staff; Bill (Sprules), Bob (Martin), Ken (Doan), and Victor (Solman), all undergraduates and, like myself, present to perform camp chores and assist with the research program. The cottage was too small for us, so we built platforms for ten-by-twelve tents on the hillside behind. These were lovely places. They were high enough to get the breeze, which kept them cooler and freer of flies, and also provided a beautiful view of the lake. Here it was only a half-mile wide, and the opposite shore was high and heavily timbered. To sit in one's tent doorway and, with binoculars, watch the forest creatures coming to water in the evening, was a continual source of pleasure. Deer we always saw and they became commonplace; less often there were bears and, rarely, a moose."

It's deeply satisfying to know that the first night at the station was spent reading aloud passages of Charles Darwin's Origin of Species. How appropriate...